April 15, 2012

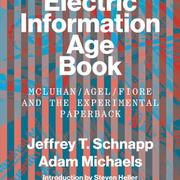

by Jeffrey Schnapp and Adam Michaels

Princeton Architectural Press, 216 pp., $19.95

Princeton Architectural Press, 216 pp., $19.95

JULIANNE VANWAGENEN

What do The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test and The Electric Information Age Book have in common? They both have Tom Wolfe, the Grateful Dead, Allen Ginsburg, revolution, counter-culture. Both center around 1967-68, and they are both a textual reproduction, retelling, documentary, of a cultural creation of the electric age. Tom Wolfe’s novelistic telling of the Merry Pranksters’ mimics, in form, the outrageousness of its content and the zeitgeist of the era. He uses groovy slang, onomatopoeia, and splashes of punctual eccentricities that reproduce, in black Latin characters on white pages, the experience, the trip, that Kesey claimed would completely transform our modes of understanding. Jeffrey Schnapp and Adam Michaels’ new release, The Electric Information Age Book, published in January 2012, is more scholarly essay than plot-based story. While Wolfe hung out in California interviewing stoners in the 1960s for his material, Schnapp, professor of Italian at Harvard University, dug through Canadian and American archives to piece together the story of the 1960s publishing flash-phenomenon/genre: the electric information age book. But that Schnapp, here, is more esoterically academic than Wolfe does not imply that the latter takes the prize for most psychedelic, most engaging, most playful, most readable. Far from it in fact, and here seems to lie the crux of what interests Schnapp and Michaels in their study of the short-lived electric-information-age genre. How can literature, even scholarly literature go beyond words to engage an audience and make an argument? The Electric Information Age Book, as well as an inventory of the entire genre, is in content an account of and in form a playful ode to Inventory Books, which began in the 1960s as a collaboration between Jerome Agel and Quentin Fiore. These two men, as Schnapp says, “put themselves forward as alternatives to traditional books, faulted by their detractors for approaching today’s tasks with yesterday’s concepts and tools. Fast-paced verbal-visual collages, intermedia hybrids, nonlinear ‘collide-o-scopic’ look-arounds aimed squarely at the contemporary scene and at younger readers.” Where the front-cover of Acid Test is certainly visually far-out, the inside is ubiquitous, black, 10 pt Helvetica. The Electric Information Age Book is alive with color throughout, it is interactive and surprising in the spirit of the books it documents. There are points where one has told the book upside-down to continue. Important ideas are highlighted in bright blue, facilitating reading, rereading, and skimming. There are photos pasted throughout that give image, more or less, to the topic of the page. Graphic artist Adam Michaels, not only adds to the scholarly argument, he tells another story, a story in which the reader is an active participant. Michael’s graphics are never captioned, sometimes context tells you their origins, other times not. This process of ‘unlabeling’ leaves the reader to assign meaning. The role of the reader, Schnapp argues, was fundamental to Agel and Fiore. Agel, a marketing man, and Fiore, a graphic designer, sought in their first book to create a “comprehensive contraction” of Marshall McLuhan’s 1964 Understanding Media, which they titled The Media is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects. This contracted-dynamic remodeling of another author’s work was used again and again by Agel. He wanted a book that was “happening,” both in the “pop-culture, street sense” and in the sense that it engaged “nonlinear, participatory, intermedia models of performance.” Readers are given the chance to read the book in different directions, at different speeds, and to different depths. But The Media is the Massage was not shock-value alone, it had a ‘massage’; namely that “there is absolutely no inevitability as long as there is a willingness to contemplate what is happening.” Agel and Fiore, as they empowered the reader/consumer to become the actor/producer, hoped to inspire great change in our ways of understanding. Their production, then, is much like cultural and artistic avant-garde manifestos, as Schnapp, an Italian Futurist scholar, says, they “explore nonlinear, reader-centered models of culture and communication both to disrupt conventional norms and to forge models of selfhood, society, and art practice, aligned with the needs of the eras of industry and information.” But can abbreviating and bedazzling texts like Agel/Fiore’s possibly promote contemplation? One could argue that the electronic-information-age form succumbs to the very distracted and shallow shortcomings of the culture it wants to subvert. Schnapp and Michaels do not make this argument. Theirs is an ‘inventory’ of the genre, rather than a judgment of it. Yet, their form mimics the playfulness and experimentation of the originals, paying tribute to the genre. The reader is left believing that Agel and Fiore, while imperfectly, were on to something that could be well reheated in the digital age.